Deaf History Month was introduced in 1997 by the National Association of the Deaf (NAD) to recognize the accomplishments of people who are deaf and hard of hearing. Unlike other cultures, Deaf culture is not associated with any native land as it is a global culture. Some may view deafness as a disability, but the Deaf world sees itself as a language minority.

Initially, Deaf History Month was observed from March 13 – April 15 each year. However, in 2022, NAD’s Deaf Culture and History Section (DCHS) and organizations representing marginalized communities recommended changing the observance dates to include the entire month of April.

Deaf History Month Timeline

Below is a timeline of several pivotal points in deaf history.

Aristotle Speaks on Deafness in 355 BCE

The existence of deafness has been known and documented since the time of philosophers. However, even the minds we deem great historical scientists understood very little about deaf individuals, writing them off as unintelligent and unable to learn.

“Those born deaf become senseless and incapable of reason.” – Aristotle, Greek Philosopher

Deaf Communities in the 16th to 18th Centuries

For over 1,800 years, deaf individuals were viewed by society no differently than how Aristotle saw them. However, this period saw the first sparks of change for deaf individuals since the start of the common era. During the 18th century, the Enlightenment in Europe brought curiosity in finding ways to educate deaf individuals, making Paris a crucible of deaf education.

Early 1500s: Girolamo Cardano (Italian physician) recognizes deaf people are cognitively functioning and have “the ability to reason.”

1550s: Pedro Ponce de Leone (Spanish Benedictine monk) becomes the first teacher of deaf individuals.

1616: G. Bonifacio publishes a treatise discussing sign language, “Of the Art of Signs,” the first book written exclusively about deaf individuals.

1653: John Wallis (English clergyman) publishes “De Loquela,” which discusses a method of teaching English and speech to deaf individuals.

1700: Johann Ammon (Swiss physician) develops and publishes methods for teaching speech and lipreading to deaf individuals called “Surdus Laquens.” His publication would result in multiple countries opening schools focused on this teaching method for deaf people.

Developments in Deaf Education in the 19th Century

In the early 1800s, deaf education was driven by an impulse to save deaf people’s souls by ensuring they could receive the word of God. During this time, deaf people mostly lived in rural areas, isolated from each other; this isolation played a large part in deaf people’s limited understanding of their capabilities. The 19th century saw huge waves of change for deaf individuals regarding education opportunities, new communication methods, and the birth of Deaf culture.

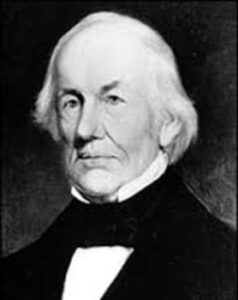

1815: American educator Thomas H. Gallaudet traveled to Europe and France, seeking methods to teach deaf individuals Christian values. While in France, Gallaudet met a deaf teacher named Laurent Clerc at an institution in Paris. Clerc taught with his hands using “signs.”

1817: Clerc accompanied Gallaudet back to America, where they opened the first permanent school for deaf children in the country and taught using French sign language. As their students learned to sign, they began blending their own signs with French Sign Language; this was the foundation of American Sign Language (ASL). Following this, new schools for deaf students began opening across America, all teaching with ASL.

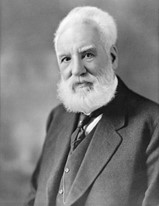

1860s: Prior to his invention of the telephone, Alexander Graham Bell taught deaf children in Boston. Bell’s wife and mother were both deaf, and he was familiar with the Deaf world and its community. Society generally sees Bell as an American hero due to his invention of the telephone, but the Deaf world has a different opinion of him.

Bell believed deaf people would lead better lives without sign language. Bell thought signing prevented deaf people from learning to speak, marked them as different, and kept them in a lower social class. Bell began pushing the idea of oralism (I.e., the oral method) which aims for deaf people to learn speech and lipreading instead of sign language, which had become the primary language of deaf individuals.

Oral schools for deaf students began to open, outlawing the use of sign language within its institutions and pushing speech training instead. These institutions were often boarding schools, where children aged four and over were dropped off, most not seeing their families for months at a time.

Speech training is based on repetition. The amount of time spent teaching deaf students how to replicate speech is time that could have been spent teaching them what hearing kids are taught in school if only their teachers were allowed to sign to them.

As deaf children attended oral schools, they would play together, share stories, invent games, pass on their customs and values, and even secretly teach each other signs. In time, this would become the foundation of Deaf culture.

1870s: Segregation affected deaf schools for decades, leading to variations of signs that differed between black deaf schools and white deaf schools. Today, ASL from different places has its own dialects depending on regions and many unique slang forms.

Bell’s invention of the telephone further excluded deaf people from society, as deaf people could not utilize the technology, not even for emergencies. That was until Robert Whitebrekt (Deaf scientist and physicist) created the Phonetype Acoustic Coupler, now known as the teletypewriter. This invention allowed deaf people to communicate over long distances by typing messages.

1880s: Discrimination against deaf people became so prevalent they founded an organization to protect themselves called the National Associate of the Deaf (NAD).

A conference was held in Milan, Italy, known as The Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf. Its delegates of mainly hearing educators voted to endorse oral education and remove sign language from classrooms. Following this conference, American schools started changing in favor of oralism, with more banning sign language by both students and teachers. This movement has been referred to as the “Dark Ages of Deaf Education in America.”

During this period, Bell began practicing the following ideologies:

- Nativism: The policy of protecting the interests of native-born inhabitants of a country against those of immigrants.

- Eugenics – The study of arranging reproduction within a human population to increase the occurrence of heritable characteristics regarded as desirable.

During this time, people began seeing deafness as an ethnic group as deaf individuals used a different language and had their own newspapers, social circles, etc. Bell’s goal was to assimilate deaf individuals into the hearing world. To accomplish this, Bell went to school boards and argued that ASL was a language borrowed from France and did not support American society.

For several years, Bell sought ways to eliminate Deaf-supporting organizations. He focused on the practice of socializing deaf people among the hearing population, again trying to separate deaf people from one another. He was concerned if deaf people continued to have children, there would be an expansion of the Deaf community.

Improvements to the Quality of Life in the 20th Century

This era in deaf history saw the ongoing suppression of sign language in schools and the increased importance of clubs and associations of Deaf people. However, this was also a positive time of change for deaf individuals, focused on civil rights, the expanded reach of Deaf culture through theatre and cinema (including the invention of closed captioning), and the recognition of ASL as a formal language.

1906: The US Civil Service stated deaf people would no longer be eligible to work for the government. Following this announcement, George W. Veditz, President of the NAD, fired a campaign against the civil service. After two years of protest, President Theodore Roosevelt repealed the act, allowing deaf people to become government employees again.

1910: The NAD began creating films to preserve sign language, showcasing sign language masters acting and telling stories. Since movies at the time were silent, deaf actors could play both deaf and hearing characters.

1924: The International Committee of Silent Sports was formed. It was later renamed The International Committee of Sports for the Deaf, and the organization still exists today.

1927: The invention of “talkies,” or movies with sound, was a disaster for deaf people. They could no longer understand movies as they watched.

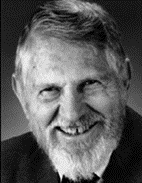

1955: American linguist William Stokoe came to Gallaudet University without any knowledge of sign language. After observing students and peers, he suggested that sign language should be considered an actual language. At the time, even Deaf people did not see signing as a proper language.

1965: Stokoe, with the help of his peers Dorothy Casterline and Carl Cronenberg, published the first ASL dictionary. This work was the first step in proving ASL as a formal language. This study helped the deaf education community realize the importance of signing in the classroom.

1967: The National Theatre of the Deaf (NTD) was established. Here, deaf actors performed plays on stage using ASL, and the shows were open to the public.

1968: The National Institute of the Deaf opened in Rochester, New York, prompting other colleges to begin offering courses in ASL and deaf culture.

1986: “Children of a Lesser God” was released as the first film where a deaf person had a lead role and used ASL throughout the film. Actress Marlee Matlin won an Academy Award for Best Actress, becoming the first deaf performer to win an Oscar.

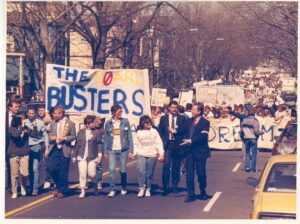

1987 – 1988: The president at Gallaudet University had resigned, and a replacement was being selected. The board of trustees at the university had chosen the three finalists for the position of president. One candidate was hearing, and the other two were deaf. The board awarded the job to Dr. Elizabeth Zinser, the only hearing candidate.

This decision sparked a protest from the students that would last for an entire week, now known as the “Deaf President Now” protest. During the duration of the protest, students blocked the entrance to the university, held multiple rallies and press conferences, took over the campus television station, and shut down classes. The students received support from across the country; even activist Jesse Jackson and then-Vice President George H.W. Bush sent letters of support.

After a week, Zinser resigned, and the board of trustees accepted all of the student body’s demands. Jordan King became the first deaf president of Gallaudet University, and all future presidents of Gallaudet University will be deaf.

“When you talk to people who can hear, and you ask them, what do you think it would be like to be a Deaf person? They start listing all the things they can’t do. I don’t think like that. Deaf people don’t think like that. We think about what we can do.“

King Jordan, President of Gallaudet University

1990: Congress passed The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), making it illegal to discriminate against people with disabilities.

21st Century Advances in the Deaf Community

The increasingly widespread use of cochlear implants, or auditory enhancement devices, has brought about a resurgence of the oralist philosophy. This resurgence is primarily due to the ongoing efforts of the Alexander Graham Bell Association. This group has a large amount of financial and political power in the medical space for deaf individuals, often targeting parents of deaf children from the moment of diagnosis and recommending steps to mainstream the child.

Research into the genetic causes of deafness can present deaf people with an existential dilemma, as potential treatments or even cures could emerge, reducing the size of Deaf communities. ASL is a beautiful language, and the Deaf community fears their language will be lost due to the rise of deaf children being mainstreamed.

“There will always be deaf people, and there will always be a need for people who are not deaf to understand deaf people.”

King Jordan, President of Gallaudet University

Deaf and Hard of Hearing Statistics

- 35M Americans are hard of hearing (HOH) to some degree; of these, an estimated 300k people are profoundly deaf.

- Approximately 17% of the population (or 36M in the US) can be classified as either deaf or hard of hearing.

- Some deafness is hereditary, and some are caused by illness or accidents; hereditary deafness is almost always one generation thick.

- Enrollment in deaf schools is declining; as a result, 85% of deaf children spend their entire education in mainstream programs in public schools.

The 90% Formula:

- 90% of deaf people are born to hearing parents.

- 90% of hearing parents have no experience with deaf people prior to giving birth to their deaf child. As a result, they are unable to communicate efficiently with their deaf child.

- 90% of deaf children raised orally cannot achieve intelligible speech despite years of intensive therapy.

- 90% of individuals born profoundly deaf end up using sign language at some point in their lives, regardless of their upbringing.

Proper Labels Within the Deaf and Hard of Hearing Communities

- Big D, Deaf – Used when referring to a particular group of deaf people who share a language, American Sign Language (ASL), and a culture.

- Little d, deaf – Used when referring to the audiological condition of not hearing.

- Hard of Hearing (HOH) – Used to denote a person with mild-to-moderate hearing loss; it can represent a deaf person who doesn’t have/want any cultural affiliation with the Deaf community or both.

Types of Sign Language

Sign language is not a universal language. American Sign Language (ASL) differs from French Sign Language (FSL), which differs from Japanese Sign Language (JSL). Also, despite preconceptions, not all deaf people use sign language.

Linguists have identified 16 characteristics of all languages, and sign language meet all of the following criteria:

- Composed of symbols.

- Symbols are organized and used systematically.

- Symbol forms may be arbitrary or iconic.

- Members of the community share the same communication system, although there may be different forms, such as accents.

- Language is productive; the number of sentences that can be made is infinite, and new messages on any topic can be produced at any time.

- Language has ways of showing the relationships between symbols. English uses prepositions, and ASL uses classifiers.

- Language has mechanisms for introducing new symbols and signals.

- Language can be used for an unrestricted number of domains.

- The symbols can be broken down into smaller parts. Meaningful units are combined to form arbitrary symbols.

- A symbol or a group of symbols can convey more than one meaning. The meaning of a word or sentence depends upon aspects of the context in which it is used.

- Language can refer to past, present, future, and non-immediate situations.

- Language changes over time.

- Language can be used to send and receive messages.

- Parts of the system must be learned from other users.

- Language users can learn other variations of the same language.

- Language users can use the language to discuss the language.

How Patient Concierge Services Benefit Deaf and Hard of Hearing Patients

Patients with rare and chronic illnesses who enroll in clinical trials must often overcome many emotional, financial, and logistical barriers to participation in a study. These burdens are increased for those in the Deaf and hard of hearing community and include the significant obstacle of communication. Most healthcare and clinical research staff do not know or understand ASL and other sign languages, leading to a lower level of comprehension of what is involved and expected of a clinical trial participant.

Patients who enroll in Clincierge’s high-touch services are paired with a Clincierge Coordinator who will remain with them through the entirety of the trial. The coordinator lives in the patient’s time zone, speaks their native language, and understands their cultural nuances. Patients receive the coordinator’s cell phone number for ease of contact but can also arrange additional communication preferences.

For deaf and hard of hearing patients, coordinators can communicate with patients via email or other preferred methods and can connect with interpreters to improve the patient’s level of communication and understanding. The coordinator works to understand the unique needs of every participant and strives to improve the patient’s experience while in the clinical trial. With this additional layer of support, members of the Deaf and hard of hearing community will be more able to enroll and remain engaged in a clinical trial throughout completion.

Additional Deaf Community Resources

- Documentary, 2007: Through Deaf Eyes

- Webinar, 2023: Barriers the Blind/Visually Impaired Community Faces in Accessing Clinical Research

- Article, 2024: Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Performs First in U.S. Gene Therapy Procedure to Treat Genetic Hearing Loss

#DeafCommunity #DeafCulture